Article by Cristina V. Burelli, founder of SOSOrinoco and ex-Senior Associate (Non resident) of CSIS published on the CSIS website on August 17, 2022 after internal reviews were completed and taken down later that same day for reasons the author does not understand nor accept.

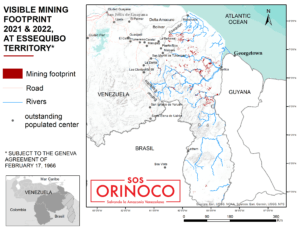

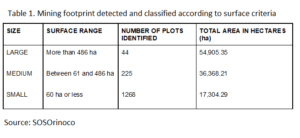

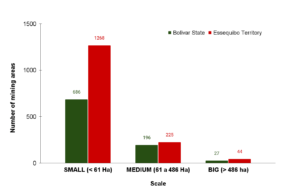

The human and environmental cost of the Nicolas Maduro regime’s Arco Minero mining policy on Venezuela has prompted SOSOrinoco, an advocacy group founded by Venezuelan experts in 2018, to take a deep dive into an even less visible area of greater Amazonia: the Essequibo territory. SOSOrinoco recently published a report on the extent of the gold mining footprint and location of the mining in the Essequibo, an area subject to the Geneva Agreement of 1966, located within Guyana’s boundaries, but claimed by Venezuela. This agreement was signed by the United Kingdom, Venezuela, and what was then the colonial government of British Guiana. Regrettably, this study shows that the magnitude of mining activity in the Essequibo territory is even larger than that of the state of Bolívar in Venezuela.

Source: Reprinted with permission from SOSOrinoco, The impact of gold mining in the Essequibo Territory and its relationship with mining in Bolívar state (Venezuela ) (Caracas: SOSOrinoco, 2022)

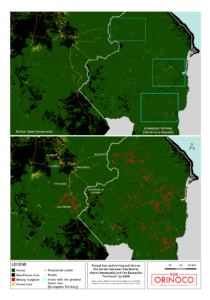

It turns out that not one, but two countries are damaging what until a few years ago was one of the world’s most biodiverse and pristine areas, located in the intersection of the Precambrian Guiana Shield and greater Amazonia. Despite the ongoing dispute, Guyana’s mining policy has promoted unsustainable medium and small gold mining west of the Essequibo River, impacting the unique ecosystems in the disputed area west of the Essequibo River. This territory’s most valuable ecosystems span nearly 15 million hectares of forest and rivers, with small (nondisruptive) indigenous settlements.

Source: Reprinted with permission from SOSOrinoco, Impact of gold mining, 15.

Guyana’s economy has run on mining gold, which is a readily available resource that the country takes advantage of in the disputed Essequibo territory. Although gold is as synonymous with the region as vast tropical forests and unique biodiversity, the Essequibo is also known for the depth of its legal complexity. As a Venezuelan territory subject to the Geneva Agreement, it is in a state of legal limbo. Venezuela is unable to exercise its sovereignty and can do little more than raise awareness about environmental and human rights abuses occurring there. Furthermore, it is a land mostly inhabited by indigenous communities, who are affected by any changes in their territories. In order to maintain any semblance of sustainable practices, all mining activity is supposed to be overseen by the Guyana Geology and Mines Commission (GGMC). An organization empowered by the government, the GGMC issues exploration permits and mining licenses of varying scales depending on sampling for precious and quarry minerals in a region. A lack of transparency, bloated administrative processes, and failure to delineate and enforce environmentally sound standards on sustainable practices has led to the system decimating the Essequibo today.

Given the issues faced by the GGMC, however, increases in mining are linked to mineral availability and logistical convenience, and not by land use or sound environmental planning.

Indigenous peoples most impacted by mining are the most immediate concern. The SOSOrinoco report states: “The gold concessions that have already been granted and the territory for which there are plans to grant concessions to small and medium-sized mining operations overlap with indigenous lands where 80% of the indigenous peoples live, in 138 communities, of which 97 are assumed to have received formal recognition of their ancestral territories.” Furthermore, these indigenous communities are endangered by Brazilian garimpeiros entering from the south by way of Lethem, and the proliferation of Venezuela’s Organized Armed Groups (OAGs) and Colombian Ejercito de Liberacion Nacional (ELN) guerrilla groups. These groups are coming over from the state of Bolívar in Venezuela and are competing for control of mines in the Essequibo, smuggling environmental pollutants like mercury and gasoline. They pose a threat for multiple reasons: First, they have weapons capable of committing atrocities against indigenous groups. Second, they have the power to strongarm populations into increasing mining activity for the express economic benefit of the OAGs, which then severely degrades the environment and living conditions of the indigenous peoples.

Source: Reprinted with permission from SOSOrinoco, Impact of gold mining, 28.

This Guyanese mining policy is having a lasting impact on the health and welfare of indigenous peoples of the Essequibo territory, and the invasion of ancestral lands by miners is irreversibly destroying traditional cultures and their very existence. According to 2017 report published by the Inter-American Development Bank, the negative impacts of unsustainable gold mining in this region have been known since the late 1990s. A combination of absence of law enforcement and lax small-scale mining standards have allowed the rampant use of mercury, deforestation, and the proliferation of unhealthy living conditions. It seems that the Georgetown government has little control over this space and does not have a sustainable development policy, nor any interest in its conservation. For example, a report by Bram Ebus and Infoamazonia revealed that mercury is widely sold and used despite the fact that Guyana is signatory to the Minamata Convention, ratified in 2014.

Granting concessions and allowing illegal activities in the Essequibo territory by the Georgetown government—all in contempt of the Geneva Agreement—are estimated to cost up to $22 billion USD in damages, stemming from deforestation, river sedimentation, and mercury pollution. It is difficult to calculate how much gold is currently produced by small and medium mining; only an estimated 50 percent of total production is declared (Blukan and Palmer, 2016). SOSOrinoco’s report concludes that Guyana, in breach of the Geneva Agreement, is unsustainably exploiting the natural resources of the claimed area. In Article V of the aforementioned Geneva Agreement, there is no renunciation or decrease of sovereignty, so until the conflict is resolved, Guyana should not grant mining or forestry concessions, nor develop projects that affect the natural resources of that territory. Unfortunately, however, it has done so and continues to do so.

Source: Reprinted with permission from SOSOrinoco, Impact of gold mining, 29.

All parties interested in the preservation of Amazonia and the Guiana Shield should be concerned by the irresponsible and unsustainable Guyanese current gold mining policy that is impacting indigenous human rights, the environment and also is in violation of international law. Furthermore, when the time comes for the judicial bodies to rule in accordance with the Geneva Agreement, Guyana’s mining policy should be considered and evaluated. In the meantime, Venezuela would be smart to propose a sustainable environmental policy for the Essequibo territory that is respectful of human and indigenous rights and that would guarantee the conservation of the the Essequibo’s biodiversity. This would require Venezuela to abolish the Orinoco Mining Arc and replace it with a sustainable mining policy, along the lines of what Venezuelan democratic governments of the twentieth century had implemented to preserve Venezuelan Amazonia and the Guiana Shield, proving that they were ahead of the times in conservation and sustainability policies.